Discoutnts, rise of corn and soybean acres put dent in crop

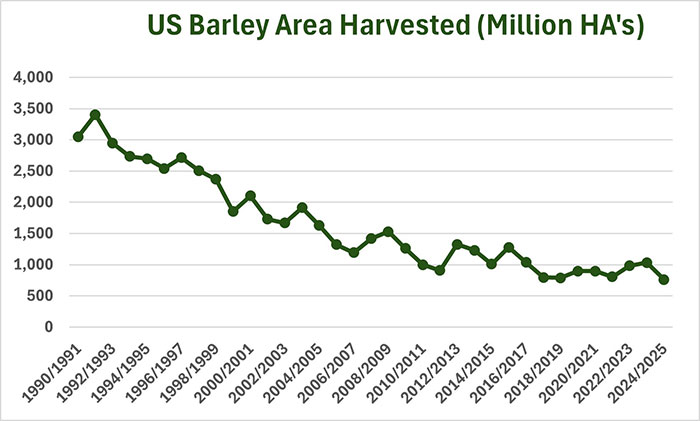

Once upon a time in the northern Plains, barley was a very significant and important crop. That was back in the days before GMO crops had been thought of. It was back in the days when the primary crops for farmers in the Dakotas, Montana, and western Minnesota were wheat, oats, and barley. Sunflowers made their appearance in the late 1970s and early 80s. The chart

shows harvested barley acres from 1990 to the current year. The decline in acres is quite amazing, from 3.5 million hectares (8.6 million acres) to just over 800,000 hectares (1.9

million acres) in 2024.

What caused the disappearance of barley as a major crop? There are numerous factors that came into play all about the same time, in the late 1980s and early 90s. There are also many and differing opinions about what caused the decline, but here are what I think are the biggest reasons:

The relationship between barley producers (farmers) and the malting barley industry was always contentious. Every farmer’s intent was to produce malting barley. Malting barley specifications include good test weight; high plump; lower protein (less than 13%); good bright color; high germination (95%); and no DON (vomitoxin). The problem, of course, is that farmers have little control over these factors. They are dependent on weather and climate throughout the growing season. Discounts from malting barley to feed barley were usually very significant. Making planting decisions based on malting barley prices carried a lot of risk. In years when barley yields and quality were good, maltsters would find reasons to downgrade barley from malting to feed. In years when barley yields and quality were not that good, barley that was feed in good years became malting barley. It was supply and demand based on what the malting industry needed at the time, and farmers had little control over the situation. Importantly, some of the grading factors could be very subjective.

Along came big advancements in corn and soybean genetics. Roundupready corn and soybeans represented major advancements in weed control and boosted yields. The improving genetics included much better short-season varieties of both corn and soybeans. These crops were suddenly adapted to the northern Plains. More importantly, corn and soybeans are not subject to

discounts for all of the various factors that barley and wheat are. Corn is corn, and soybeans are soybeans. There are no worries about protein, color, plump, or falling numbers.

Farmers were looking for alternatives to barley and, in some cases, wheat. North Dakota corn acres went from 900,000 in 1991 to 3.8 million in 2024. North Dakota soybean acres went from 600,000 acres in 1991 to 6.9 million acres in 2024. Those are amazing numbers, and there were similar shifts in the surrounding northern Plains states.

The malting barley industry moved from “open” markets to offering malting barley contracts to farmers. These contracts contained several different pricing points and factors. Some were based on a relationship to the Chicago wheat futures contract. The intent was to maintain enough barley acres to ensure a supply of malting barley while offering the producer a more “guaranteed” new crop price structure.

The sharp increase in the corn and soybean planting trend across the Dakotas and western Minnesota pushed barley acres into Montana and Northern Idaho, where GMO corn and soybeans were not as readily adaptable.

There were multiple side effects of the steep drop in barley production. Domestic feed barley consumption has almost disappeared, replaced by corn and soybean meal. Livestock numbers across the northern Plains have also gotten much smaller over the years. U.S. exports of feed barley were almost 96 million bushels in 1992. They will be less than 500,000 bushels

this marketing year.

The beer industry has also changed greatly over the last 10 to 15 years. The craft beer industry now represents almost 15% of total U.S. beer production. The majority of that growth has come since 2015. Total beer production in the U.S. was down 5% in 2023. Craft beer production was down 1%. Beer consumption has been declining. So has the demand for malting barley. The expansion in the craft beer industry has also brought expansion in small malting companies servicing the craft beer producers. The old-line, major malting companies are struggling, while the new and tiny malting companies are doing well.

Barley is now a specialty crop similar to dry beans, food grade soybeans, etc. Oats now fall into the same classification. The malting industry has consolidated. Some major facilities have closed (Spiritwood, N.D.). For Washington, a bright spot in this gloomy outlook is the potential for new malt barley varieties bred for the Pacific Northwest that give farmers a better bet at consistent quality to meet craft beer industry standards. Time will tell. That may give you one more reason to “drink local!”

This article originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.

Mike Krueger

Mike Krueger is founder of The Money Farm, a grain marketing advisory service located in Fargo, N.D., now owned and run by Allison Thompson. Krueger, a former Wheat Watch columnist for 12 years, is semiretired. He still provides commodity groups with market insights and observations. He is a past director of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange and a senior analyst for World Perspectives, a Washington, D.C., agricultural consulting group.