“Precision farming involves using technology and data at one or more of the many stages of farming,” writes Vijayalaxmi Kinhal from CID Bio-Science Inc., an agricultural and environmental plant research instrument design and manufacturing company based in Camas, Wash.

In simpler terms, it’s all about getting more return on investment per acre, said Ryan Tippett, director of product innovation at The McGregor Company.

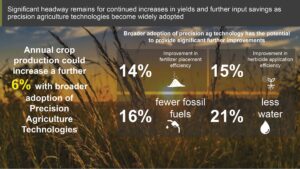

There are environmental and sustainability benefits too. The adoption of precision farming practices to date has resulted in roughly 30 million fewer pounds of herbicide being applied to fields across the country. With broader adoption of precision practices, another 48 million pounds could be spared, according to the Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM). And that’s just one input. AEM’s study also identified significant reductions in fertilizer, fossil fuels and water use as a result of wider adoption of precision farming.

“If today’s American farmer wants to continue thriving, it’s important to become more efficient. Technology plays directly into that,” Nick Tindall said. Tindall is AEM’s senior director of regulatory affairs and ag policy.

Finding square [zone] one

The possibilities for tracking data on a farm are endless, and industry is just starting to “connect the dots” and decipher how much of that data is actually useful.

“They estimate less than 20 percent,” Bill Lindsey, director of precision services at The McGregor Company said. “And, currently, not very many people collect data, and those that do, don’t always know what to do with it.”

For The McGregor Company, this means finding ways to harness the power of big data and looking for solutions specific to the Pacific Northwest. This will make them a valuable resource as more Washington farmers look to optimize their farming practices into the future.

“To me, it’s all about looking at the variability of your soil and treating accordingly,” Lindsey said. This method, called zoning, allows a grower to use variable-rate application to optimize their inputs at all stages of the growing cycle based on the specific needs of each zone, in the amounts needed and timed based on the demand curve of each crop.

“Every crop has a demand curve for nutrients, and knowing the timing of that curve is key to inputs,” Tippett said.

Precision farming is a process, not an immediate return. Farmers operating on slim margins are hesitant to try new things. Equipment is expensive—there are a lot of hand-me-downs still working in Washington agriculture. Some old combines are not even equipped to measure yield, and others that do have no way to save the data for later reference. Plus, dealing with landowners can be a hurdle. Investing in the soil can be tricky if you only own 200 acres out of 3,000. But all is not lost.

“Compact, handheld devices, smart sensors, mobile apps and small drones can bring the benefits of precision farming even to small farmers. Often, the benefits to small farmers can mean using just 20 percent of the fertilizers or pesticides,” Kinhal writes. “In some cases, very little technology is needed.”

Farmers who track even just a few variables, without too much extra effort, can optimize their land for increased yield while keeping costs low. The simple act of recording yield data by field or region and tracking this over time is the best starting point for farmers to dip their toe into precision farming.

Getting your feet wet

According to Lindsey, the main factors impacting yield are crop variety, soil, inputs and weather, but, he said, you can’t manage what you don’t measure. The following are his list of the top five steps farmers can take right now to start using their farm’s data to their advantage.

SOIL SAMPLES. This should not be a composite sample of the whole field. The soil samples need to be from smaller divisions to have meaning; zone sampling, or grid sampling, is a more effective sampling method when you are looking to use it to make fertilizing decisions. You do not necessarily need to sample every year; every four years will give you trend data that is still meaningful. The timing of the sample and the sampling locations needs to be consistent year to year to allow accurate comparisons. Then, do the math and see if your soil is better or worse.

TISSUE SAMPLES. If properly timed, tissue samples can tell you “right now” what you need to know, and combined with soil sample data, they can help you see trends over time. It is important to sample and act on the plant’s nutrient demand curve.

WEATHER. Tracking weather that affects the growth of your crop will help you to understand what yield factors were affected during the year. Specifically, looking at rainfall, high and low daily temperature, cloudy vs. sunny days and growing degree day heat units for the particular crop will help with understanding the “why” of yield.

APPLICATIONS. Simple things such as seed variety, planting date, harvest date, fertilizer and chemical applications—product, amount and date—and to get better detail, collect more complex things like seeds per pound on each variety you plant, GPS scouting data, as-applied data and expense data.

YIELD DATA. This doesn’t have to be from a yield monitor; even simple yield data like scale tickets for each field can be used to make whole field comparisons. A yield monitor changes the scale from field size to acre, or even down to the combine footprint depending on how detailed you want to get. Yield monitors don’t have to be pricey; depending on what else you want to do with the system, a simple yield monitor that uses your cell phone for a screen can be very reasonable and accurate.

The key to tracking data is to look for trends. With so many factors playing into a harvest, there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. Luckily, Pacific Northwest farmers also have a growing number of resources to help them dive into their data. Work with your local agronomist, Lindsey said.

This article originally appeared in the February 2022 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.