By Marija Savic, graduate student, Washington State University Weed Science

I am a graduate student in the Washington State University (WSU) weed science program. I have been working on the management of smooth scouringrush for the past two years with Dr. Drew Lyon and his research associate, Dr. Mark Thorne.

After getting a bachelor’s degree in agriculture at the University of Belgrade, Serbia, I was an intern at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln West Central Research Extension and Education Center in North Platte, where I participated in laboratory and field research on troublesome Midwestern weeds. Research has always been my primary interest, and a direction I wanted to take. After a year of interning, I decided to start a graduate program with Dr. Lyon. Before starting at WSU, I had never heard about the scouringrushes, especially not as a troublesome weed in row crops. It did intrigue and surprise me.

Smooth scouringrush (Equisetum laevigatum) belongs to the botanical family Equisetaceae, which has only one living genus — Equisetum, commonly known as horsetails. Equisetum species are true survivors and may be the oldest nonflowering vascular plants existing on Earth. The fact that even dinosaurs ate them as a primary food source speaks for itself. Equisetum species date from the Paleozoic (542 to 251 million years ago), and they have survived what many species have not — natural disasters, fires and all sorts of disturbances, including present human activity.

Smooth scouringrush and two other Equisetum species — field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) and scouringrush (Equisetum hyemale) are all native to the North American continent. The name scouringrush comes from how the plant has been used by humans throughout history — the native population traditionally used stems to scrub and clean dishes. These scouring properties come from a high silica content in scouringrush stems, which gives them a rough surface. All Equisetum species, including smooth scouringrush, are creeping perennials with a deep underground rhizomatous (underground stems) system. This system is very successful and provides a means for rapid vegetative spread, up to 20 inches per growing season. The root system can reach more than nine feet in depth. As a nonflowering plant, smooth scouringrush does not produce seeds. Rather, it reproduces sexually only via spores, similar to ferns and mosses. However, this type of reproduction is rare in environments such as Eastern Washington — dry, non-humid and with a relatively cold early spring.

Smooth scouringrush is a troublesome weed in no-till systems of the Pacific Northwest. It is believed that repeated deep tillage (plowing) prior to the adoption of no-till practices, contributed to the spread of smooth scouringrush rhizomes. Plowing, however, may have reduced shallow rhizomes from which stems emerged, thus leaving the species under the radar. Once no-till systems were adopted, shallow rhizomes developed and produced aboveground stems with spore-bearing cones on top (Figure 1).

In a March 2021 Wheat Life article, Dr. Lyon provided results of earlier research on the management of smooth scouringrush. Over the past several years, we have learned a few more things about this particular plant.

Since the last update, we conducted several studies using higher application rates of glyphosate (96 fl. oz/acre of RT3) in fallow because preliminary observations were promising. One consistent observation from these studies was that high rates of glyphosate can reduce smooth scouringrush infestation in the following year, but only if applied at the right stage/time and with the proper surfactant. My research focus was to test the hypothesis that the addition of an organosilicone surfactant, which is known to greatly increase droplet spread, to glyphosate facilitates stomatal flooding of the herbicide solution and, therefore, increases herbicide uptake and efficacy.

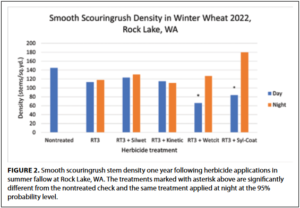

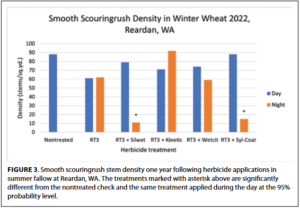

To test this hypothesis, we established field studies in 2021 at Reardan and Rock Lake. We applied glyphosate alone or tank-mixed with one of four different adjuvants and applied treatments during the day and night. The assumption that stomata are open during the day and closed at night was based on the available literature. Selected adjuvants were Silwet L77, Kinetic, Wetcit, and Syl-Coat. Silwet L77 and Syl-Coat are organosilicone surfactants. Wetcit is a citrus, alcohol-based surfactant, and Kinetic is a blend of organosilicone and nonionic surfactant. When high rates of glyphosate were applied earlier in the season (June-July at Rock Lake), the addition of Syl-Coat or Wetcit increased herbicide efficacy when applied during the day, while glyphosate alone did not appear different from the non-treated check (Figure 2). However, when Silwet L77 and Syl-Coat were applied later in the year (August at Reardan), herbicide efficacy only increased when these treatments were applied at night (Figure 3). These results call into question our original hypothesis that organosilicone surfactants improve glyphosate activity by facilitating stomatal flooding. However, it is possible that the hot, dry conditions in August 2021 at Reardan resulted in either stomatal closure during the day or rapid drying of the spread-out droplet, resulting in poor control under those conditions.

From one of our 2020 studies, we found that silica content in smooth scouringrush stems increases from spring to late summer. This may affect treatment performance later in the season by decreasing herbicide uptake and efficacy. Early season applications (early summer) are generally more successful than late summer and fall applications due to plant senescence, increased silica content in stems and potential drought stress. Hot, dry weather in late summer may also contribute to faster droplet evaporation from the plant surface, which may result in nighttime applications being more successful than daytime applications. Drought stress may also cause the stomata opening cycle to shift to nighttime. Generally, daytime applications of glyphosate tank-mixed with an organosilicone or alcohol-based surfactant in early summer, when temperatures tend to be lower and humidity higher, should be preferred for smooth scouringrush control in chemical fallow.

Management of perennial weeds, including smooth scouringrush, is a marathon rather than a sprint. Many characteristics of this plant that has been on Earth for a very long time are still unknown, but we can keep it out of our fields with a long-term management approach, persistence and the application of multiple control strategies.

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.

Marija Savic

Marija Savic is a graduate student in the Washington State University weed science program working under Dr. Drew Lyon and Dr. Mark Thorne. Read more about WSU Weed Science.