Public wheat breeders continue legacy of excellence

By Seth Truscott

From William Jasper Spillman’s first release in the early 1900s to the newest cultivars reaching farms this year, breeders at Washington State University have kept Washington wheat competitive for well over a century.

Times may change, but the university’s public wheat breeding program remains committed to an independent, far-seeing role that supports the growers of today and tomorrow.

“We are stewards who are here for the long haul,” said Professor Rich Koenig, chair of the WSU Grain Royalty Advisory Committee. “We’ve been entrusted with the future of the wheat industry.”

A legacy of innovation

The story of Washington wheat breeding began with Spillman, who arrived at the newly established Washington Agricultural College in 1894 as its sixth faculty member.

A WSU plant scientist, mathematician, and — at the time — the university’s undefeated football coach, Spillman sought to improve economic health for farmers by producing useful varieties of wheat. From crosses made in 1899, he showed how combinations of traits could make wheats that are better adapted to the soils and climates of Washington. Spillman went on to work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, where he helped establish a forerunner of today’s Extension system, but not before breeding WSU’s first six club wheat releases.

“Traditionally, all the wheat grown in the Pacific Northwest was club wheat,” said Kim Garland-Campbell, a Pullman, Wash.-based USDA research geneticist and club wheat breeder.

Club wheat arrived in the Inland Northwest by way of California during the 19th century. It became a Northwest export, destined for Asian markets that paid a premium for its prime milling and end-use qualities.

For decades, fungal diseases like bunt and smut were among the biggest challenges for Northwest wheat growers. Agronomy and plant breeding instructor Edward Gaines, who joined the WSU program in 1912, bred more fungus-resistant hard winter and club wheats.

After Northwest growers urged Congress to fund a cooperative regional wheat improvement program in the late 1920s, one of Gaines’ former students, Orville Vogel, was hired as a USDA wheat breeder in 1931.

“Vogel and Spillman were true renaissance men,” said Mike Pumphrey, WSU’s spring wheat breeder. “They were engineers and economists as well as breeders.”

Since Vogel’s day, scientists from WSU and USDA have worked together to improve wheat quality, hardiness, and productivity. Researchers collaborate on projects, share ideas, and co-advise students. Their work is also supported by the Washington Grain Commission, which has funded wheat and barley breeding since the 1960s in a six-decade partnership.

Working with the grain commission and the USDA, WSU built the Plant Growth Facility, which has become a national model of cooperation. WSU’s two-cent royalty on new wheat varieties, established in 2012, helped pay for the facility and is now supporting breeding research, training, and infrastructure.

Bringing in valued traits

Before Vogel, most commercial wheat grew on tall, stately stalks. A USDA researcher at WSU Pullman for 42 years, he bred new semi-dwarf wheat plants that ploughed more energy into their heads of grain, boosting yields by as much as 25%. Vogel named his revolutionary variety “Gaines,” in honor of his teacher. It was released in 1961.

“Gaines hit like a storm,” Garland-Campbell said. The main Northwest wheat at the time was “Omar,” a club that had been hit hard by stripe rust. “Orville had this new line that yielded better, and it was ready to go.”

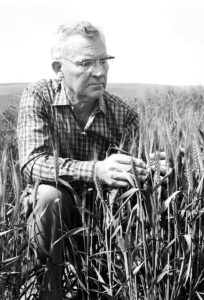

Vogel’s former technician and WSU scientist Clarence Peterson, USDA scientist and Vogel hire Robert Allan, and other researchers continued the mission to breed cereals for diverse local climates and pest and disease challenges that might otherwise have been overlooked by private wheat breeders.

Peterson worked with WSU plant pathologist George Bruehl to release Sprague, the first snow mold-resistant winter wheat, in 1972. Daws, released in 1976, was bred for winter hardiness, a trait maintained in current wheats. In 1988, Allan released Madsen and Hyak, the first strawbreaker foot rot-resistant varieties. Allan’s 1991 club wheat, Rely, included eight different types of stripe rust resistance.

Peterson’s 1990 cultivar Eltan and breeder Ed Donaldson’s 2000 release Finley are winter wheats with excellent emergence from deep sowing, another characteristic that WSU scientists have brought into modern varieties. Calvin Konzak released 24 cultivars of spring oats, durum wheat, soft white spring and hard red spring wheat. His cultivar Penewawa was the most widely grown spring wheat in the Pacific Northwest for many years.

The chain continued as breeders Stephen Jones, Kim Kidwell, and Garland-Campbell took over management of breeding programs from Peterson and Donaldson, Konzak, and Allan. Molecular geneticist Kulvinder Gill also released several varieties, including Curiosity CL+ and Mela CL+. Today, more than 50 named varieties have debuted since 1995 and counting.

Over past decades, the WSU breeding program received multiple offers to merge with private companies. WSU has always chosen to maintain its independence, preserving the investment that the institution, the Washington Grain Commission, and growers have made throughout the past 120 years.

“Washington’s ability to export wheat is based on end-use quality, and that quality is phenomenal because growers hold WSU to a high standard,” Koenig said. “We can’t make solely short-term decisions. If we were to lose the rights to our germplasm, we’d lose control over quality and opportunities to breed for the specific needs of Washington.”

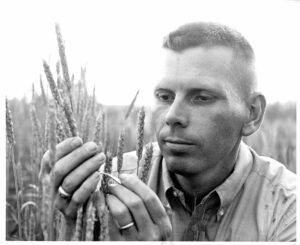

Circa 2009, WSU continued its commitment to Washington wheat by filling vacant winter and spring wheat breeding positions. Maintaining the program ensures that advanced germplasm will continue to be available to Washington growers.

“We bring so many components together into a single product, from drought and disease tolerance to end-use quality,” said Carter, the O.A. Vogel Endowed Chair in Winter Wheat Breeding and Genetics. “And we get to see the improvement to people’s livelihoods. I think that’s pretty amazing.”

“We always play the long game,” Pumphrey added. “We want those who come after us to be better prepared than we were when we began.”

Benefits beyond new cultivars

Public breeders do more than develop new wheats. They share knowledge with growers and industry partners, attend trade tours to understand the market and finesse end-use quality, and teach the next generation of plant breeders, researchers, and business operators.

“One reason I’m at the university is the opportunity to interact with students and pass on my legacy,” Carter said. “I’ve had great mentors in my life, and I try to be the same for my students.”

The team’s genetic improvements uplift the science of wheat breeding in the public and private sectors. Serving the public, WSU breeders consider what lies ahead, tomorrow and 50 years from now.

“There’s no standing still,” Pumphrey said. “We have to intentionally maintain genetic diversity in the long run.”

WSU’s wheat breeding teams are working to develop varieties that consistently succeed across changing climates and widely varying production zones. They must also consider the changes coming to their discipline and the region, from evolving diseases and pests to revolutionary hybrids and gene-editing tools.

“Some of the crosses I make have no chance of producing a new variety,” Pumphrey said. “But they produce something solid that I can add to future crosses, making the next release that much better.”

Pumphrey, Carter, and Garland-Campbell see themselves as inheritors of the tradition set by their predecessors.

“Each one of us along the way has remained focused on the grower,” Carter said. “Each brought in new germplasm that improved important traits like disease resistance, yield, or end-use quality. We’re continually building on our legacy.”

Seth Truscott

Seth Truscott is a public relations and communications coordinator for the Washington State University College of Agriculture, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences, and a contributing author for Wheat Life Magazine.