The significance of the weed seedbank to wheat production in the Pacific Northwest

By Ian Burke

The weed seedbank is a crucial component of agricultural and natural ecosystems, playing a significant role in shaping weed communities, agricultural productivity, and conservation practices. Understanding the dynamics of weed seedbanks is essential for effective weed management strategies and sustainable land-use practices. Indeed, assessing the status of the seedbank on a field-by-field basis may be the best metric for assessing future crop rotation or conservation plans. The problem is enormous — in our recent work assessing the status of the weed seedbank, the numbers of seeds we are finding often exceed a billion per acre. Adaptation is a numbers game, just like in wheat breeding, and weeds exist in our wheat fields in numbers that are astonishing. It’s no wonder that weeds adapt so quickly to our inputs!

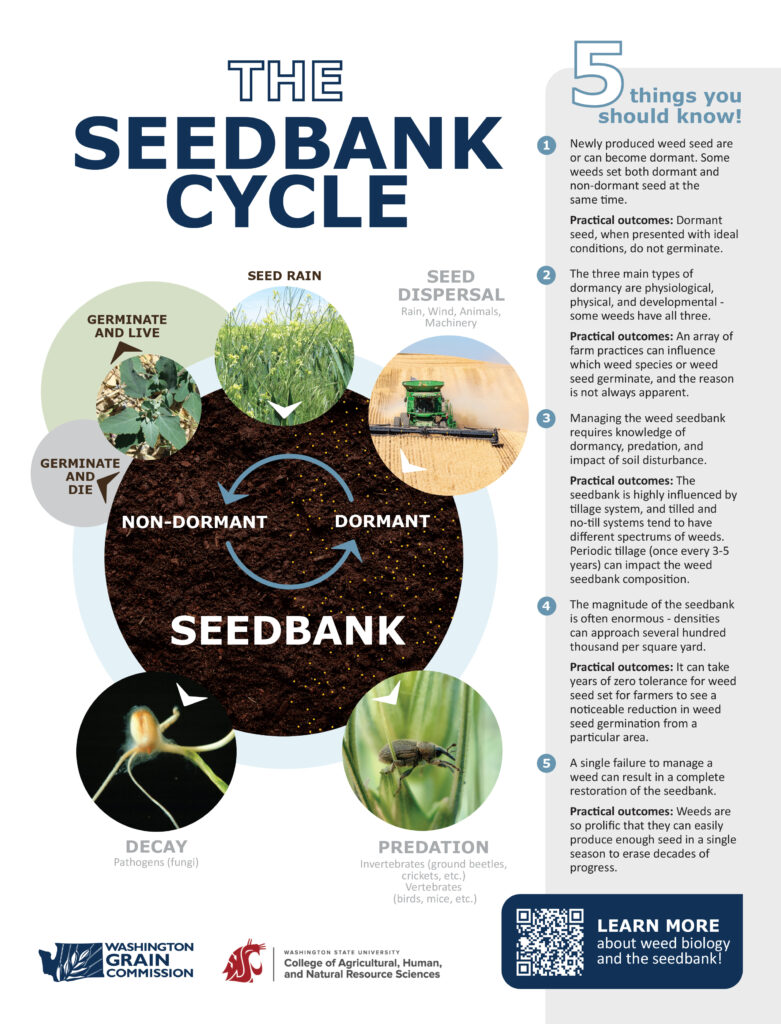

The weed seedbank refers to the collection of dormant weed seeds present in the soil seed reservoir. These seeds originate from various weed species and can persist in the soil for extended periods, ranging from months to several to many years, depending on environmental conditions and seed characteristics. The composition of the weed seedbank is influenced by factors such as seed dispersal mechanisms, soil type, land management practices, and environmental conditions.

Seeds within the weed seedbank exhibit varying levels of dormancy, which affect their germination potential. Dormancy mechanisms, such as physical, physiological, and morphological dormancy, regulate the timing and conditions required for seed germination. Environmental cues, including temperature, moisture, light, and soil disturbance, play crucial roles in breaking seed dormancy and triggering germination. There’s consensus that only about 4% of the seedbank germinates every year — the aboveground growth suppresses additional germination in the same way as a crop canopy.

The weed seedbank is dynamic, with seeds continuously entering, persisting, and exiting the soil seed reservoir. Seed input occurs through seed rain from mature weed plants and seed dispersal by wind, water, animals, and human activities such as tillage and crop cultivation. Seed persistence in the soil is influenced by factors like seed burial depth, soil microbial activity, predation, and environmental conditions. Seed output occurs through seed decay, predation by seed-eating organisms, and seedling emergence. There’s a growing recognition that we need to reduce or ideally completely eliminate seed production every season. Frustratingly, soil and moisture conditions in the Pacific Northwest appear to be suited to longer weed seedbank persistence.

The weed seedbank plays a crucial role in shaping weed community dynamics, species composition, and biodiversity in our wheat fields. In wheat production systems, the weed seedbank poses significant challenges to crop production by reducing yields, competing with crops for resources, harboring pests and diseases, and increasing weed management costs.

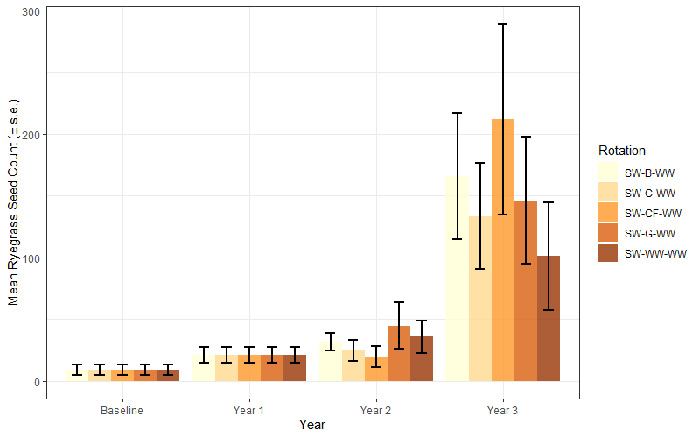

Effective weed management strategies aim to minimize the impact of the weed seedbank on agricultural productivity, ecosystem health, and long-term system resiliency. Management practices that promote soil conservation and restoration can influence the dynamics of the weed seedbank, too. Practices such as reduced or no-till enhance soil health, structure, and biodiversity, potentially reducing the persistence and viability of weed seeds in the soil. Dr. Drew Lyon and I have been working to address how to manage weeds from a weed seedbank perspective. From attempting to stimulate weed seed germination with growth regulators to harvest weed seed control, our efforts have been at best frustrating. Dormancy and shattering are key attributes for the most successful weeds, and our systems are highly constrained by climate and the need for soil stabilization.

Despite advances in weed management research and technology, challenges remain in effectively managing the weed seedbank. Factors such as herbicide resistance, adaptation, and variation in climate pose ongoing challenges to targeting the weed seedbank. Future research directions include exploring novel weed management strategies, understanding seedbank ecology in changing environments, and simply developing methods to rapidly and accurately quantify the weed seedbank.

The weed seedbank plays a critical role in agricultural systems, influencing weed community dynamics, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. Understanding the dynamics of the weed seedbank is essential for developing effective weed management strategies, promoting sustainable land-use practices, and conserving soil and ecosystem health. Continued research and innovation are necessary to address the challenges posed by weed seedbanks and ensure the resilience and productivity of our wheat production systems in the Pacific Northwest and in Washington.

Download the PDF: The seedbank cycle.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.

Ian C. Burke, Ph.D.

Ian Burke, Ph.D., holds the J. Cook Endowed Chair of Wheat Research at Washington State University. His research program is focused on basic aspects of weed biology and ecology with the goal of integrating such information into practical and economical methods of managing weeds in the environment. Read more about Dr. Burke.