Following the management of low falling numbers throughout the ‘grain chain'

By Alison Thompson and Amber Hauvermale

The dynamic landscape of logistics for wheat export in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) make up the complex system we call the “grain chain.” To improve methods for testing and managing low falling numbers, it is important to first understand the history of the current system. Read our article that introduced this series here.

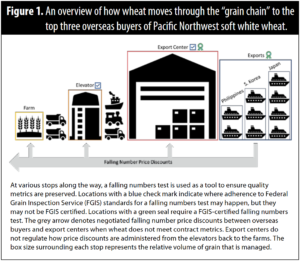

The farm-to-export process is streamlined for efficiency to increase PNW grain value in the global market. The chain starts at the farm with the important step of variety selection, which impacts grain management downstream. The logistics of grain management become complicated as varieties with differing quality are mixed upon receival at elevators and export terminals. Smaller capacity, regional, “country” elevators and larger, consolidated grain cooperatives are used to collect, store, and handle nearly 250 million bushels of soft white and club wheat in the PNW annually. Truck, rail, and barge shipping networks transport grain to export terminals to fulfill contracts negotiated earlier in the year, typically 120 days prior to harvest. The term, “turning the house,” describes how efficiently a location fills, empties, and refills its elevators again, and locations that turn the house most efficiently can capture a larger share of total revenues. But low falling numbers and the available tools to manage this problem threaten this efficiency.

Falling numbers at the elevator

Sales contracts drive grain management. A falling number is one of the quality market specifications for export sales contracts. If the falling number specified cannot be met, the export centers will renegotiate sales prices. During our interviews last spring, everyone identified the same logistical challenges tied to postharvest management of grain with low falling numbers — regardless of operation size or geographical footprint, challenges were slow testing and limited storage that constrained segregation of good grain from bad. To tackle these challenges, grain handlers will use early testing and blending. There are two types of blending. Unintentional blending is simply the result of our current receival process, where thousands of bushels of different varieties, with unknown quality are delivered to a few central locations (elevators). In contrast, intentional blending occurs when different lots of grain with known quality are mixed to meet contract specifications and is used at elevator and export centers.

To regulate unintentional blending, early testing for falling numbers is routine. If low falling numbers are detected, testing continues throughout harvest and attempts to segregate based on location or even by grower may occur. Common practice is to send composite samples to outside labs, and falling number results are reported back within 24-48 hours. These results are used to determine any related price discounts. Compared to other tests that measure protein and moisture content in under 90 seconds, a 24-48-hour timeline is extremely slow and impractical for use with every truckload. The lack of a rapid falling number test limits the ability for grain segregation and can increase the time to turn the house.

Only two companies interviewed were performing onsite falling number tests for intentional blending. These onsite tests are performed specifically to blend lots or bins for export, not to assess price discounts. Testing procedures vary by elevator based on whether the grain will be resold to another, larger warehouse or managed by the same company all the way to the export terminal.

Blending and testing steps may be repeated six to eight times before export because of the exponential increase in volume as grain travels to its final destination (Figure 1). While intentional blending is routinely used, there are important considerations that affect successful blending. These include barometric pressure and protein, which can cause unexpected falling numbers if not properly accounted for, and a larger amount of good grain is needed to blend away bad grain.

Blending and testing steps may be repeated six to eight times before export because of the exponential increase in volume as grain travels to its final destination (Figure 1). While intentional blending is routinely used, there are important considerations that affect successful blending. These include barometric pressure and protein, which can cause unexpected falling numbers if not properly accounted for, and a larger amount of good grain is needed to blend away bad grain.

Testing and requirements

During our interviews, we were made aware of distrust in the falling number method due to contrasting results across the grain chain. To better understand the falling number test within the grain chain, we spoke with members of the grain industry, including state and private testing facilities. While we confirmed the method is regulated and monitored at the federal level, Federal Grain Inspection Service (FGIS) regulations may not necessarily be applied at the state and local levels.

Understanding the regulations, how and when they are applied, and how to interpret them involves four key aspects:

- FGIS protocol states a valid test must have two samples from the same lot run at the same time. These samples must be within 5% of their average and be mathematically corrected for moisture content and barometric pressure. A valid test is not required for intentional blending; however, it is required for all other purposes, including assessing price discounts.

- Falling number testing facilities are not required to be FGIS certified. Noncertified facilities can still provide valid tests following the FGIS protocol but may not include the ability to audit test results with an officiating system or provide consistent, repeatable results that are common with certified locations.

- A FGIS-certified falling number test is required at time of export to ensure market contract specifications are met. If the FGIS-certified number does not meet contract specifications, export centers will reblend, when possible, or establish a discounted sales price based on market demand. For example, a 25-cent discount per 25 seconds varies based on the overall health of the crop in the given year.

- When contracts are renegotiated due to low falling numbers, FGIS and the export centers do not control how price discounts are assigned and distributed back to growers; this is at the discretion of the elevators.

Management of low falling numbers varies and depends on who is managing the grain and for what purpose. Limitations in the current falling number test, storage capacity, and other logistics force the industry to be reactive, and opportunities to be proactive are limited. The falling number method is regulated at the federal level, and a FGIS-certified falling number is only required at time of export.

The next article will highlight the common needs communicated, along with current research focused on improving pre- and postmanagement opportunities that mitigate loss due to low falling numbers.

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.