Breeding winter barley for dryland growing regions of the Pacific Northwest

Is there a future for winter barley production across the dryland growing regions of the Pacific Northwest (PNW)? There is no clear answer to this question, as many factors must be worked out, and no winter barley varieties adapted to this region are currently available or under production. As a barley geneticist, this question is fascinating. Many of the agronomic obstacles facing winter barley production in nontraditional growing regions can be overcome through genetics, but major questions concerning markets, profitability, and production need to be worked out before barley is a viable option for farmers. Thus, these factors also come into consideration when deciding on the genetic targets in the breeding program.

The Washington State University (WSU) winter barley breeding program story starts with the fact that barley in Washington is predominantly spring feed, grown on dryland production regions within winter wheat rotations. Also, barley acreage has been in a major decline due to lower profitability compared to spring wheat. However, the overall lower productivity of spring wheat and cereals that experienced low precipitation and untimely high temperature events over the last few growing seasons suggests that a winter barley option could provide profitable yields under these adverse environmental conditions. If winter barley could consistently produce — I’ve heard the magic number of 3 tons per acre — this crop would be a profitable option for dryland farmers.

The WSU barley breeding program initiated the winter breeding program in 2021 with the initial goal of providing dryland winter malt barley varieties, as Great Western Malting expressed interest in contracting winter malt barley in the dryland growing regions of Washington state. This decision was based on the yield and quality advantages winter malt barley has over spring-sown malting barley, due to better utilization of stored soil moisture and avoiding the summer heat during grain fill. However, as Great Western Malting closed their malting facility in Vancouver, Wash., they did not contract any barley in Washington state in 2025 — essentially pulling the rug out from under the program’s aim of developing the winter and spring varieties recommended by the American Malting Barley Association.

That said, the superior-yielding experimental lines within the program would be excellent feed barley lines, while the high-yielding lines with adequate malt quality could be considered dual-purpose as both feed and craft malt barley. The advantage of winter over spring barley during years of drought and heat is evident by the overall yield differential observed between the WSU winter and spring barley experimental lines during the 2025 growing seasons. The top 20 winter experimental lines in the advanced yield trials at Spillman Agronomy Farm in Pullman, Wash., delivered average yields of 4.46 tons per acre, while the top 20 spring experimental lines brought average yields of 2.56 tons per acre. Of course, winter was mild in 2024, which means these winter trials did not suffer any significant survival issues. Despite mild winters becoming more common in the region, cold tolerance (i.e., winter hardiness) remains a major concern for winter barley varieties adapted to the PNW’s dryland growing regions.

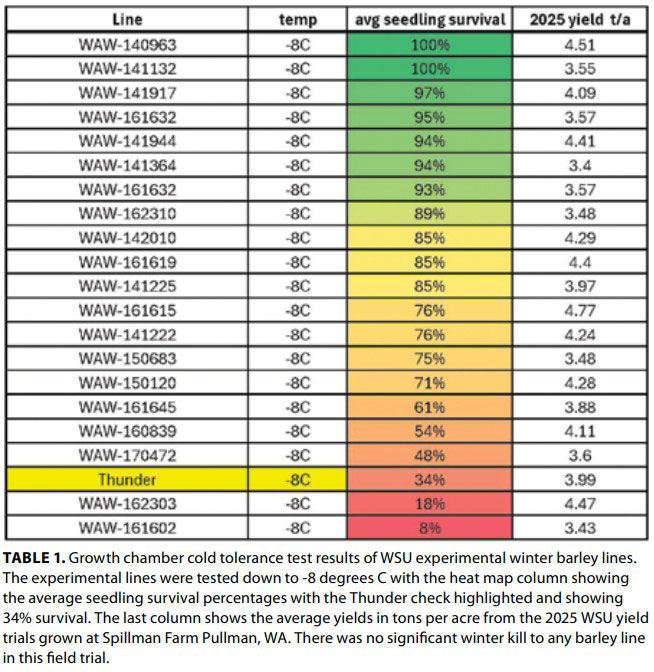

Cold tolerance is the major constraint to winter barley production extending north, due to the lack of cold-tolerant winter barley genotypes that can handle the abiotic stresses — which means stress from nonliving components, like temperature — encountered during harsh winters. Although the genetics for cold tolerance are present in the barley germplasm pool, barley has been far behind wheat in selecting for cold hardiness. The development of winter hardy lines is a major goal that must be achieved to bring Washington farmers adapted varieties for our region, which is why introducing these genetics into the WSU barley breeding program is a major objective. We have already begun transferring cold tolerance genetics (called introgression) into the breeding program and, in collaboration with Dr. Kim Garland-Campbell’s U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service’s wheat breeding program, can efficiently have this material evaluated through grant funding provided by the Washington Grain Commission. Dr. Garland-Campbell’s group developed a method of screening winter wheat varieties in growth chambers and modified the parameters for winter barley. Her program has been evaluating promising winter barley lines for the last two years. This research has helped identify lines with increased cold hardiness within the program (see Table 1). Additionally, this testing is enabling us to produce quality data on cold tolerance traits (phenotypes), on both natural and crossbred (biparental) populations, which will enable us to identify regions and genes that can be utilized as genetic markers for program selection. As this cold tolerance testing within the winter wheat program has had good correlation with winter survival in the field, we are confident that these tests will ultimately identify cold-tolerant winter barley lines that translate to

Cold tolerance is the major constraint to winter barley production extending north, due to the lack of cold-tolerant winter barley genotypes that can handle the abiotic stresses — which means stress from nonliving components, like temperature — encountered during harsh winters. Although the genetics for cold tolerance are present in the barley germplasm pool, barley has been far behind wheat in selecting for cold hardiness. The development of winter hardy lines is a major goal that must be achieved to bring Washington farmers adapted varieties for our region, which is why introducing these genetics into the WSU barley breeding program is a major objective. We have already begun transferring cold tolerance genetics (called introgression) into the breeding program and, in collaboration with Dr. Kim Garland-Campbell’s U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service’s wheat breeding program, can efficiently have this material evaluated through grant funding provided by the Washington Grain Commission. Dr. Garland-Campbell’s group developed a method of screening winter wheat varieties in growth chambers and modified the parameters for winter barley. Her program has been evaluating promising winter barley lines for the last two years. This research has helped identify lines with increased cold hardiness within the program (see Table 1). Additionally, this testing is enabling us to produce quality data on cold tolerance traits (phenotypes), on both natural and crossbred (biparental) populations, which will enable us to identify regions and genes that can be utilized as genetic markers for program selection. As this cold tolerance testing within the winter wheat program has had good correlation with winter survival in the field, we are confident that these tests will ultimately identify cold-tolerant winter barley lines that translate to

winter survival under field conditions.

Summer trade team activity

Although resources for WSU’s barley breeding program have proportionately favored the development of malt barley varieties over the last six years, the loss of markets in the region has brought that resource allocation into question, shifting back to a traditional focus on feed barley varieties. However, the program will continue developing spring and winter malt barley to meet the demands of the local craft malting, brewing, and distilling industries. As there is a growing market for food barley, there will also be considerable effort and resources directed at developing biofortified (crops bred to increase their nutritional value) winter and spring food barley varieties.

As a geneticist and breeder, developing winter barley varieties is an exciting challenge. We are making headway toward achieving our goal of winter-hardy feed, malt, and food barley varieties that could provide farmers with greater profitability and sustainability. However, many questions still linger concerning the adoption of winter barley varieties into the traditional rotations — heavily impacted by availability, markets, and prices. So once again, this article is an open invitation for farmers, end users, and seed dealers to provide your feedback on what barley classes you believe WSU’s barley breeding program should focus on to get more barley acreage on the map.

This article originally appeared in the October issue of Wheat Life Magazine.