Weather patterns, susceptible varieties behind problem

By Alison Thompson and Amber Hauvermale

In April of 2023, my colleague, Amber Hauvermale, and I set out on a falling numbers fact-finding mission with a twofold purpose. The first was for me to introduce myself as the new U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) scientist hired in Pullman to work on falling numbers, to meet those impacted by low falling numbers, learn about the challenges they face, and identify what tools and information are needed to help mitigate future impacts of low falling numbers. (Read more about me from the April Wheat Life Magazine).

The second was for Amber, a member of the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at Washington State University, to share information about the development of a new rapid test to detect alpha-amylase activity, the starch-degrading enzyme responsible for low falling numbers, to gauge industry interest, and to identify early adopters of the new technology. The rapid test development is part of a project supported by the Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research. (More about this in the June Wheat Life Magazine).

After several interviews, it became clear to us that there is a gap in understanding among some grower groups regarding the falling number method, its purpose, and its history with Pacific Northwest (PNW) grain. As a result, a second round of interviews was conducted to provide clarity. This article is the first in a three-part series to share what we learned over the course of these 18 interviews.

Purpose and history of falling numbers in the PNW grain chain

A “falling number” is the number of seconds it takes a stirrer to fall through a slurry or gravy made from wheat meal. The thicker the slurry, the longer it takes the stirrer to fall, which results in a high falling number. Thin slurries are due to starch degradation by the alpha-amylase enzyme and result in a low falling number. Flour with degraded starch yields baked products like cakes, breads, and cookies that are sticky and misshapen, which are less marketable to consumers.

The falling number method to test for alpha-amylase activity was first published in 1964 by Herald Perten, a cereal chemist from Sweden. Dr. Perten’s original study was conducted to help millers and bakers reliably measure alpha-amylase activity in flour for the purpose of adjusting to desirable levels for the final baked product. It is important to note that some alpha-amylase activity is necessary for bread baking. In fact, Perten found that the ideal range of falling numbers for bread was between 200 and 250 seconds. So, the questions become, when did the

standard for falling numbers change from 250 to 300 seconds and why?

To answer these questions, a brief dive into the history of PNW grain in the global market is needed. One of the first recorded sales of PNW flour from Walla Walla was in 1868 to a British vessel bound for Liverpool. By the turn of the century, 100 vessels were coming to Portland, Ore., for PNW grain bound for Japan and China. In 1959, the PNW was producing far more soft white wheat than the U.S. and current trade partners could consume, thus the Western Wheat Associates was formed to help expand international markets.

In 1980, due to the changing global marketplace and demand for all market-class grain produced in the U.S., Western Wheat Associates joined with a similar organization in the Great Plains to become U.S. Wheat Associates. It is also at this time that farmer associations approached the Federal Grain Inspection Services (FGIS), founded in 1946, to start testing for grain quality metrics including falling numbers. By the mid-1980s, the falling number test became part of the FGIS standard protocol and part of the market contract specifications for U.S. grain.

In 1992, a mild, preharvest sprouting (PHS) event throughout the PNW precipitated the development of a stricter falling number standard of 300 seconds, as well as discounts of $.01 per second. These new standards were established in a collective effort by farmer associations, grain elevators, the marketing arm for U.S. wheat, and overseas buyers to minimize risk. The 300 second standard became part of the market contract specifications in August of that year. In 1993, a severe and widespread PHS event occurred in the PNW, and the new 300 second specification was strictly enforced. This enforcement was driven mainly by Japan, who remains the top buyer of PNW soft white wheat today, followed by South Korea and the Philippines.

The wheat quality metrics, established in the 1980s, have been the primary selling points for PNW soft white wheat on the global market ever since. To the overseas buyer, these metrics are important to ensure a consistent, quality product for their consumer market, which is typically confectionery items like cakes and cookies. Very few countries in the world choose to consistently meet these quality metrics for soft white wheat.

Insights to falling numbers in the PNW

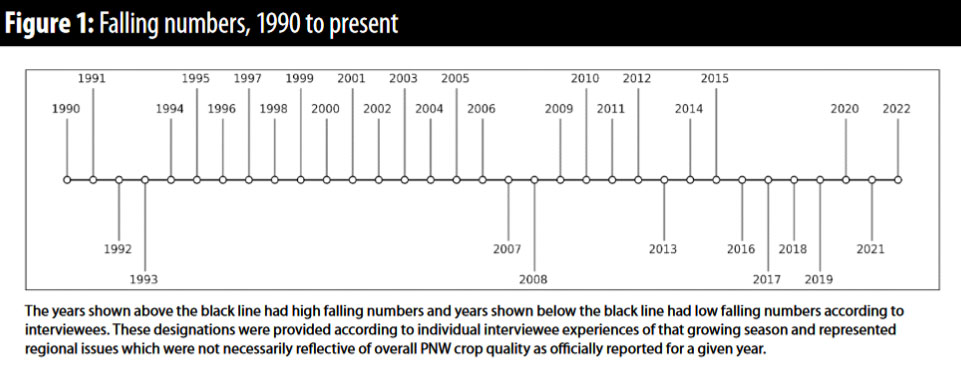

So, why has the falling number metric of 300 seconds become so difficult for PNW farmers to meet in the last 10 years? Every organization that was interviewed indicated a year, or several years, where low falling numbers had been detected (see Figure 1). While these localized events did not negatively impact the overall quality of PNW wheat, they may have caused economic loss at the level of individual farms.

Research to date suggests there are two culprits: changing weather patterns resulting in PHS, which is sprouting of grain due to rain before harvest, and varieties susceptible to late maturity alpha-amylase (LMA). LMA is the result of a cool, wet period during the early dough development stage of wheat. It is unclear if susceptibility to LMA has always been present in PNW varieties and the variable weather patterns that cause this problem just didn’t occur, or if susceptibility was introduced at some point in a germplasm exchange. Either way, incorporating resistance to LMA and PHS is a focus for PNW breeders to help mitigate these problems.

To conclude, the falling numbers method to test for alpha-amylase activity has been established since the method first was published in 1964. At that time, the falling numbers standard was 250 seconds. In the early 1980s, U.S. farmer associations approached FGIS to incorporate falling numbers into their standard practice for grain quality to be more competitive in the global marketplace. In the early 1990s, a series of PHS events across the PNW resulted in falling number discounts leading to a shift from 250 to 300 seconds as a standard for market contract specifications.

Low falling numbers has been a recurring problem since 2007 and has become more widespread with the discovery of LMA in 2013. Wheat breeders in the PNW are working to incorporate resistance to PHS and LMA in released varieties to help mitigate the economic impact of PHS and LMA at the regional level.

The next article will focus on how low falling numbers is currently managed throughout the “grain chain,” from the country elevators to the export centers.

This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.