By Dani Gelardi

What is soil health?

Growers who have been managing soils for decades may be surprised by the recent emergence of “soil health.” Instead, they remember when it was referred to as “soil fertility,” and the primary goal was to manage soils to support crop growth. Growers may also remember when soil fertility was replaced by “soil quality.” Then the motivation shifted to managing soils, given inherent soil properties, to support crop growth and minimize degradation. The shift from fertility to quality paved the way for thinking about soil sustainability. It also made room for tailoring management to the unique properties of different soils, from the slope of the land to the texture or organic matter content of the soil. This latest phase—soil health—has pushed our thinking about soils beyond agriculture. The goal is now to steward soil ecology, given inherent soil properties, to support multiple soil functions and minimize degradation. Soil health recognizes that soils have a function beyond crop growth. They filter air and water, store carbon and can reduce the effects of climate change, contain cultural significance, support recreation and provide wildlife habitat. But of course, they grow crops! And in the process, they ensure food security and thriving rural economies.

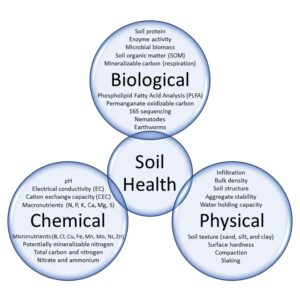

Soil health also newly recognizes the living nature of soil and the important role that microorganisms play in soil functioning. This focus on biology has led to many new kinds of soil tests, which seek to identify and measure the quantity, activity and role of soil microbes. These biological measurements have been added to an already large list of soil health indicators (Figure 1). There are the traditional tests for soil chemistry, which include pH, electrical conductivity (EC) and macro- and micro-nutrients. There are also physical tests, which include water holding capacity, texture and measures of compaction such as bulk density. Together, these biological, chemical and physical indicators can help us understand more about the health of a soil, and how well the soil can perform its various functions.

What soil health measurements should I

monitor?

The Washington Soil Health Initiative (WaSHI), a partnership between Washington State University (WSU), the State Conservation Commission (SCC) and the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA), has set out to answer this very question. In a program called the State of the Soils Assessment, WaSHI partners are measuring the biological, chemical and physical properties of soils across the state. To date, more than 100 fields in dryland agriculture have been sampled, with 200 more planned for 2022. WaSHI partners intend to find out which soil health measurements are most meaningful for Washington producers. Do some tests correlate with yield better than others? Are some measurements irrelevant in a dryland context? “Soil health scoring curves” are currently available to help producers determine if their soils are above or below average for specific measurements. However, these curves are largely based on corn and soy fields across the Midwest. Using data from the State of the Soils Assessment, WaSHI partners are calibrating these curves for Washington-specific climates and cropping systems. Scoring curves for dryland agriculture are currently under production.

What can improved soil health do for my farm?

After an extensive, two-year needs assessment, the Washington State Soil Health Roadmap was released in October 2021. In this document, dryland producers described soil management challenges that reduce crop yield and soil sustainability: wind and water erosion, low water holding capacity, compaction due to the adoption of no-till practices, low fertility, acidification and pressure from weeds and disease. While the focus on soil health may be new, WSU researchers have been studying these problems for a long time. A 2021 research article estimated that 17.1 percent of winter wheat and 19.4 percent of spring wheat in Washington is lost due to weeds, costing producers around $139.3 million in lost revenue over 10 years.[1] A 2019 study from Oregon State University showed that weed pressure can be significantly reduced by intensifying crop rotations or growing a spring crop instead of fallowing.[2] Covering the soil surface[3] and increasing the time in which live roots are present[2] Covering the soil surface[4] may also improve soil health parameters, such as water-holding capacity, fertility and resistance to erosion. Soil erosion creates air quality problems, as well as a loss of fertility and soil carbon. In another example of improved soil health management, a 2020 WSU study demonstrated that leaving full stands of wheat, canola or chickpea residues can reduce soil loss by 53 to 73 percent.[5]

While growers and researchers are clear on the soil management challenges in contemporary dryland production, more and more is being learned about possible solutions. These solutions may include crop intensification and alternative residue management, or practices like cover cropping, integrating livestock or adding compost or lime. Many questions remain about these practices, however—what dryland regions will they work best for? How much will they cost to implement? How long until the investment pays off? Through research, outreach and extension, WaSHI partners are working on answers to these questions as well.

What’s next for WaSHI and dryland production?

By linking State of the Soils data with grower survey responses, WaSHI partners are looking for trends in what management strategies lead to “high” or “low” soil health scores. WSDA also hopes to estimate the economic costs and benefits of different practices, and whether specific strategies helped reduce the impacts of the 2021 drought. This survey will be issued in early 2022, and all Washington wheat growers are encouraged to respond. Check the WSDA website in early spring for more information. Ultimately, data from this and other WaSHI projects will support Sustainable Farms and Fields. This SCC-led program will offer grants to make it easier and more affordable for growers to experiment with practices that increase soil carbon and improve soil health.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Wheat Life Magazine.

Dani Gelardi, Ph.D.

Dani Gelardi is an agricultural scientist with extensive experience managing projects in government, at universities, and within environmental nonprofits. Gelardi has a strong track record of conducting impactful science resulting in concrete policy outcomes. Currently, she is the senior soil scientist for Washington State Department of Agriculture, leading the statewide Soil Health Initiative to measure and improve soil health across cropping systems and regions in Washington. She is also a Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research Fellow (2019-2022).